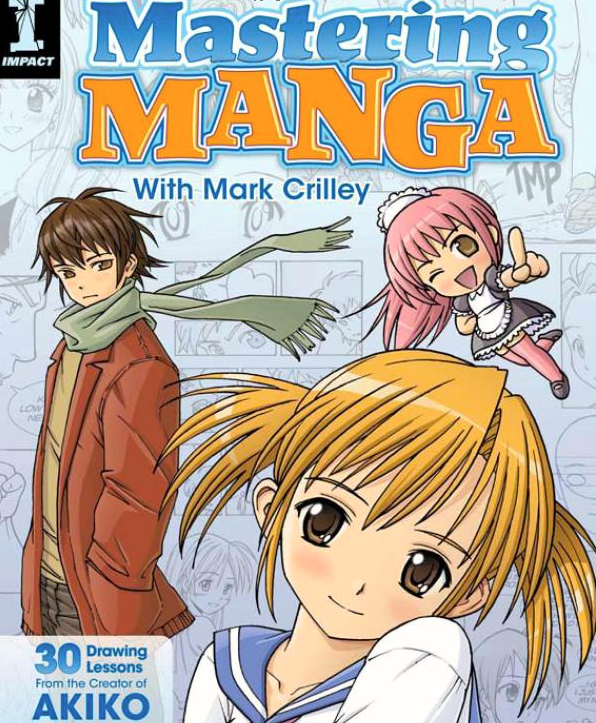

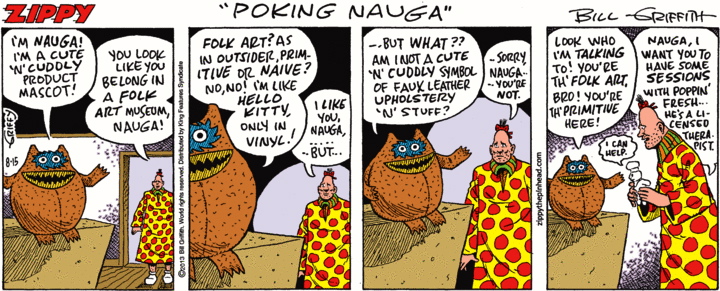

In a set of notecards, a reproduction of a sensuous painting, The Soul of the Rose (1908) by John William Waterhouse:

![]() (#1)

(#1)

The woman is smelling the rose, but she’s close to kissing it, close to treating it as a romantic partner (in which case the rose is a symbol of the lover’s mouth). Other, more carnal, interpretations are available to modern audiences, for whom the rose can serve as a symbol of either the vagina or the anus.

But first, on Waterhouse and this work. From Wikipedia:

John William Waterhouse (born between January and April 1849; died 10 February 1917) was an English painter known for working in the Pre-Raphaelite style. He worked several decades after the breakup of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which had seen its heyday in the mid-nineteenth century, leading him to have gained the moniker of “the modern Pre-Raphaelite”. Borrowing stylistic influences not only from the earlier Pre-Raphaelites but also from his contemporaries, the Impressionists, his artworks were known for their depictions of women from both ancient Greek mythology and Arthurian legend.

And from the beginning of an extended analysis of the painting:

Unlike a large proportion of Waterhouse’s other work, The Soul of the Rose is not a scene taken from a famous or ancient tale of love. Instead it is a study of a woman in a garden thought to be based on the work of Alfred Lord Tennyson. It’s important to keep in mind the themes of many of Waterhouse’s other works though, as similar themes of lost or unrequited love resonate in this picture.

Romance and Sensuality: Waterhouse often incorporated a great sense of sensuality in his women, whether in the form of naked flesh or simply a delicate look. Restrained sexuality and longing for an invisible love are key themes in The Soul of the Rose and the artist portrays the woman in the picture without any obvious sexuality, but her position against the wall and her delicate hand indicate subtle sensuality.

Victorian Values: Many of Waterhouse’s paintings are very telling of the place women had in society during his time. Victorian Britain was, for women, a place where for the first time, they started to be politically active and were able to vote and had other political rights that they had previously been denied.

Many of Waterhouse’s women are trapped or imprisoned and he seems fascinated by the idea of a woman who is powerful yet restrained. This may have been what he observed with women with high public profiles during his lifetime. The Soul of the Rose is no exception to this, as the woman is shown against a brick wall, her pleasure is nature and her thoughts of a love that was.

The rose — in particular, in the form of a rosette — appears frequently as a carnal symbol in pornographic writing, sometimes standing for the vagina but very frequently for the anus. On the rosette:

A rosette is a round, stylized flower design, used extensively in sculptural objects from antiquity. Appearing in Mesopotamia and used to decorate the funeral stele in Ancient Greece. Adopted later in Romaneseque and Renaissance, and also common in the art of Central Asia, spreading as far as India where it is used as a decorative motif in Greco-Buddhist art.

The rosette derives from the natural shape of a rosette in botany, formed by leaves radiating out from the stem of a plant and visible even after the flowers have withered. The formalised flower motif is often in carved in stone or wood to create decorative ornaments for architecture and furniture. A common motif in metalworking, jewelry design and the applied arts at the intersection of two materials, or to form a decorative border. (Wikipedia link)

Rosettes are commonly used for awards, ribbons, and recognitions. Here’s an elaborate architectural example:

![]() (#2)

(#2)

On to anal rosettes. Many examples, from both straight and gay porn writing. One of each:

His finger fucked back and forth for a few more moments before he pulled it out and positioned his cock at her rosette. She pushed back as best she could as he pressed forward, and she winced as his cock popped past her sphincter and into her ass. (link)

I pulled a condom from my pocket and slipped it over my cock. Kneeling behind him, I positioned the tip of my cock against his rosette. The condom was lubricated; Rafe wasn’t. (link)

And from AZBlogX, on image #6 in this posting:

from the Michael Lucas raunch/kink archives, this ad for a feature on assholes as a fetish or paraphilia (most gay men appreciate butts, but only some are deeply moved by contemplating assholes), with hard-working pornstar Adam Killian showing off (on a hunky buddy) the object of this specific desire [photo here, with the caption:]

THE EXEMPLARY ASSHOLE

Ed’s perfect

Rosette wins gold

Medals at the

State Fair.

A very careful composition. Note especially the cleft just above the asshole paired with the one in the lower back, and the role Killian’s face and spread hand play in the organization of the picture. (The star within the O of ASSHOLES matching the anal rosette is crude, but then how much subtlety could you ask for in a flick about fuckholes?)

This brings me, of course, to Jean Genet’s The Miracle of the Rose, in which anal intercourse figures prominently:

The Miracle of the Rose (in French: Miracle de la rose) is a 1946 book by Jean Genet about experiences as a detainee in Mettray Penal Colony and Fontevrault prison – although there is no direct evidence of Genet ever having been imprisoned in the latter establishment. This autobiographical work has a non-linear structure: stories from Genet’s adolescence are mixed in with his experiences as a thirty-year-old man at Fontevrault prison. At Mettray, Genet describes homosexual erotic desires for his fellow adolescent detainees. There is also a fantastical dimension to the narrative, particularly in Fontevrault passages concerning a prisoner called Harcamone who is condemned to death for murder. Genet idolises Harcamone and writes poetically about the rare occasions on which he catches a glimpse of this character. Genet was detained in Mettray Penal Colony between 2 September 1926 and 1 March 1929, after which, at the age of 18, he joined the Foreign Legion. (Wikipedia link)

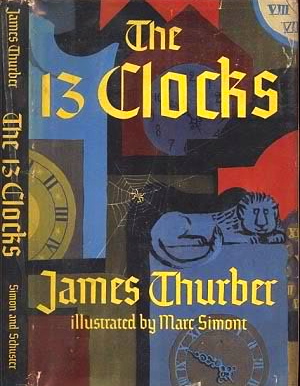

And from there to Querelle de Brest:

Querelle of Brest (French: Querelle de Brest) is a novel by the French writer Jean Genet. It was first published anonymously in 1947 and limited to 460 numbered copies. It is set in the midst of the port town of Brest, where sailors and the sea are associated with murder, and its protagonist is Georges Querelle. The novel formed the basis for Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s last film, Querelle (1982).

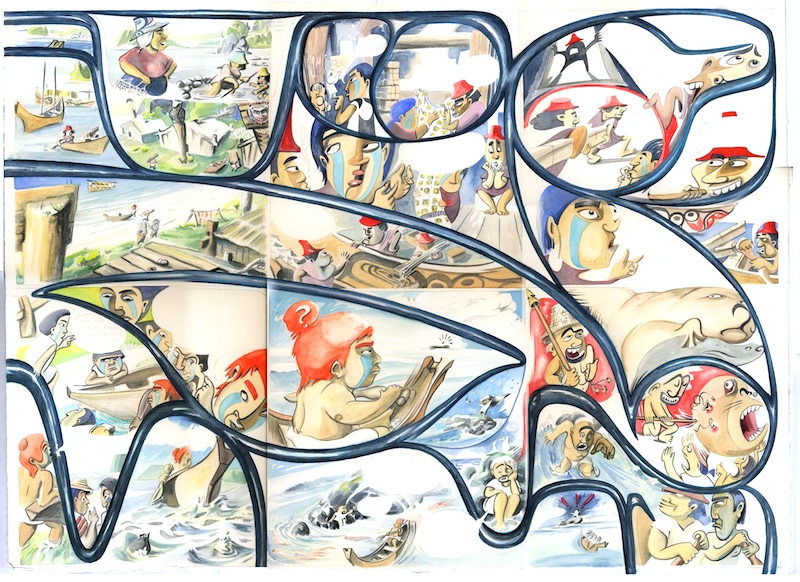

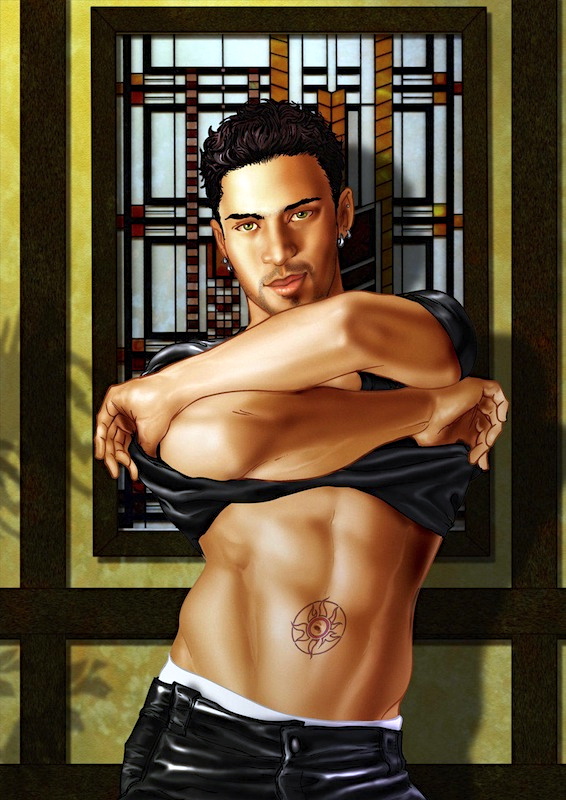

The notorious poster for the film:

![]() (#3)

(#3)

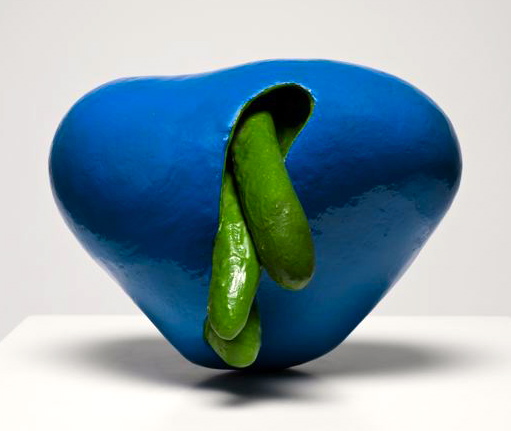

Outrageously phallic. There are other sexy posters for the film, but none this extreme. The most famous, though, is Andy Warhol’s:

![]() (#4)

(#4)

![]()

![]()

(#2)

(#2)